The importance of social connection and culturally sensitive self-management tools to support patients managing chronic health conditions has been emphasised in a recent study by Menzies.

The study of the digital health tool – the Stay Strong app – explored its suitability to support self-management for First Nations people with kidney failure. The research has highlighted the benefits of setting quality of life goals for patients undergoing renal dialysis.

The Stay Strong app is a holistic wellbeing intervention tool, already found to have high acceptability and feasibility among First Nations people.

The Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative (AIMhi) in the Northern Territory has conducted foundational work over 2 decades. It has developed culturally responsive wellbeing tools, like the Stay Strong app, through grass roots involvement with First Nations people and guidance by First Nations Expert Reference Groups.

The new paper published online in BMC Nephrology, explores the suitability of the AIMhi Stay Strong app to support self-management by measuring the readiness of participants to engage in goal setting.

Menzies Head of Wellbeing Preventable and Chronic Diseases Division and lead author, Professor Tricia Nagel, said the paper followed the publication of findings from a clinical trial. That trial examined whether the Stay Strong app improved mental health and wellbeing for First Nations people receiving haemodialysis.

“The paper had 2 objectives: the first was to explore the suitability of the Stay Strong app as a self-management tool in End Stage Kidney Disease as shown by the readiness of participants to engage in goal setting, and the second objective was to give voice to participants priorities and values as revealed through their self-management goals,” Prof Nagel said.

Data collected during the clinical trial between February 2017 and March 2019 looked at 156 participants receiving haemodialysis for kidney failure in Alice Springs and Darwin.

Almost all participants 147 (94%) received a Stay Strong session. Of these, 135 (92%) attended at least 2 sessions, and 83 (56%) set more than one wellbeing goal.

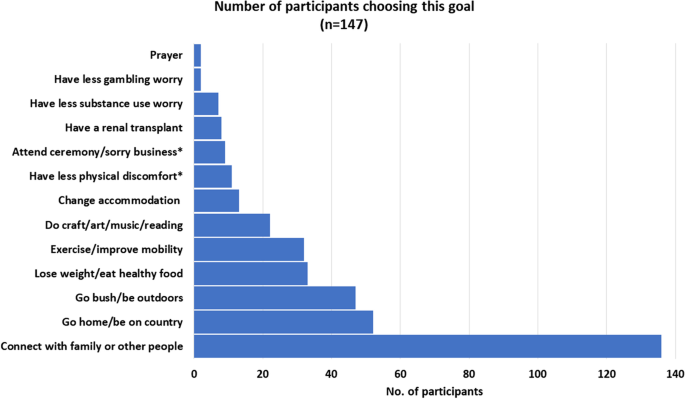

Using a deductive approach to manifest content, 13 categories of goals were identified. The 3 most common were: ‘connect with family or other people’, ‘go bush/ be outdoors’ and ‘go home/be on Country’.

Image caption: A graph illustrates the 13 categories of goals and how commonly they were chosen by participants.

Analysis identified 3 themes throughout the goals: social and emotional wellbeing, physical health, and cultural connection.

The Stay Strong approach emphasises the importance of allowing participants to lead responses. Researchers worked with participants during a 20-minute session which had the key elements of a face-to-face semi-structured interview.

The interview was designed to assist in establishing rapport by sitting side-by-side to view the shared screen, thus avoiding direct eye contact if preferred.

A further element to strengthen therapeutic alliance was the discussion prior to goal setting of important relationships and strengths.

The training for researchers also emphasised that direct questions can be experienced as challenging. Instead, practitioners were encouraged to show the relevant images to participants and simply ask, for example: ‘Are any of these worries for you?’

In total, 262 separate goals and the reasons for choosing that goal, were entered into the app, with most participants setting more than one goal.

Many separate goals incorporated more than one type of category, for example: ‘connect with people’ often also included a goal to ‘go home’ or ‘to Country’. A goal to ‘exercise’ often included plans to ‘go hunting’.

Exploration of goal data through content analysis resulted in 373 individual goals and 13 distinct but interlinked categories. The most frequent was to ‘connect with family or other people’.

“This study demonstrates the potential for a culturally responsive tool, already found to have high acceptability and feasibility among First Nations people, to be used in provision of a person-centred approach to self-management,” Prof Nagel said.

“Despite physical illness, low mood, and high distress, dialysis participants engaged actively in this self-management intervention.”

The vast majority chose to attend follow up sessions. Most chose more than one goal, and most chose more than one step to that goal.

The goals chosen aligned with the holistic view of health of First Nations peoples documented elsewhere. Connection to culture, land and family were interwoven throughout.

Social connection was chosen more than twice as often as other goals.

“This need for social contact and family connection, and preference for treatment at home or visits home - often to their remote community - is well aligned with established evidence of the sense of isolation and displacement from family, country, and identity caused by relocation for dialysis,” Prof Nagel said.

“The findings confirm that while biomedical models must focus on the mechanics of illness, First Nations people also prioritise social connection, family, country, and cultural identity.”

The study demonstrated that the Stay Strong app can be used as a chronic condition self-management tool for First Nations people, which helps fill the gap regarding culturally responsive self-management support tools currently available.

**

The paper titled: The Stay Strong app as a self-management tool for first nations people with chronic kidney disease: a qualitative study – is available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02856-x

More information about the Stay Strong app is available on Menzies’s website and you can help support our research through donations to Menzies’ fundraising campaigns.