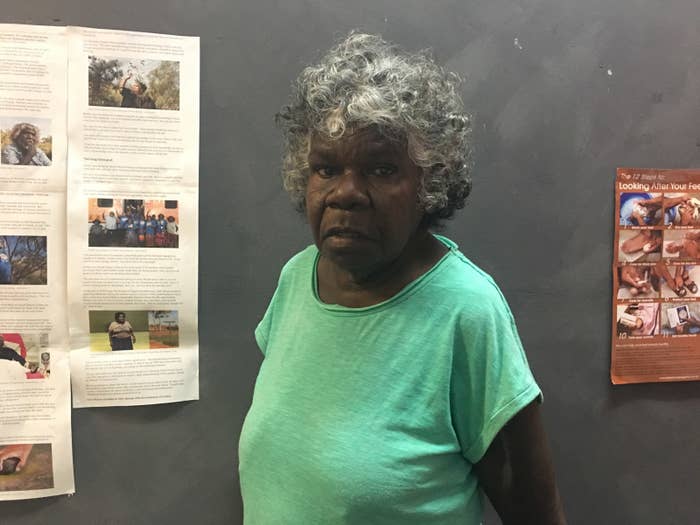

Gloria Friday “just cried” when she first went on dialysis.

“I am a strong person for the community and for my family,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I’m a role model. I like to play sports. I just cried because I can’t do any of them things any more, because of my dialysis.”

Kidney disease meant the chatty Borroloola Elder had to travel 700km from her small, remote community to Darwin for dialysis, leaving behind her partner and family, and her job as a teacher at the local school.

Arriving in Darwin in 2015, the 61-year-old faced a question that confronts many other Aboriginal people coming from community to urban centres for dialysis, condemning some to homelessness: where would she live while getting the life-saving treatment?

Although housing in Borroloola can be low-quality and overcrowded, Friday shared a four-bedroom, two-bathroom house with her partner Graham and other family.

But in Darwin she found herself with no house and very little money, as she began her gruelling dialysis schedule of three four-and-a-half-hour sessions per week. It left her hungry and weak, as well as being homesick and lonely.

She spent her first year in Darwin at the Daisy Yarmirr Hostel, or the “Daisy Y”. It's run by Aboriginal Hostels Limited (AHL), a non-profit, federal government-owned temporary accommodation service for Indigenous people.

Although Friday applied for public housing, the waitlist for a one-bedroom place in Darwin is six to eight years long. "We understand that you can't just come rocking to Darwin and expect to get a house straight away", Friday said. But by the time renal patients get public housing, "some of us mightn’t be alive". The average survival rate for Northern Territory renal patients is six years.

The shortage of public housing is one reason the Northern Territory's homelessness rate is 12 times the national average. More than 1 in 20 (5.6%) of the population has no accommodation.

Some of those are people on dialysis, a hugely taxing medical treatment that end-stage kidney disease patients need indefinitely to survive, unless they receive a transplant. A 2011 study of renal patients in Alice Springs found that 15-20% did not have secure accommodation.

The NT housing department told BuzzFeed News people with serious medical problems could apply for priority housing, but that wait times varied based on the number of applications and location. The NT government has also partnered with the Commonwealth to build ten family-based dwellings (eight in Alice Springs and two in Tennant Creek) so that patients with end stage kidney disease could live in town with their families or carers.

For Friday, private rentals were also out of reach. Affordability is one challenge, but Friday also says she has been rejected from every place she has applied for. She believes many landlords don’t want to rent to Aboriginal people.

AHL’s subsidised rent of $31 a night, or $434 a fortnight, is below market rate. But for people like Friday, it can still be expensive.

Unable to work, Friday initially relied on Patient Travel, an NT government scheme covering accommodation costs for kidney patients travelling for treatment for up to eight weeks. Then for a “long period of time” she had to get by on Newstart — the job-seeking allowance that left only a tiny amount after AHL rent — before being accepted for the Disability Support Pension (DSP).

This delay in receiving the DSP is not unusual, according to Stefanie Puszka, a researcher with the Menzies School of Health Research and the Australian National University, who has authored a research brief for the Deeble Institute for Health Policy Research on improving access to housing for Indigenous renal patients.

While renal patients are usually eligible for the DSP, Puszka said, they can face long waits, commonly up to six months. In one case, a woman Puszka knew waited for over a year. Unable to afford a hostel, and with nowhere else go, she became homeless.

A spokesperson for the department of social services told BuzzFeed News that some dialysis patients are able to work and therefore ineligible for the DSP, which requires a person to be unable to work for 15 or more hours per week for at least the next two years. "DSP assessments can be complex and involve examination and assessment of extensive raw medical evidence that must be submitted with the claim for payment," the spokesperson said.

Homelessness and housing instability can exacerbate patients' health problems.

"I know doctors who say they’re more worried about patients being homeless than about their diabetes," said Puszka. "That might actually have a bigger impact on their life, and their ability to attend treatment, to get proper sleep, to eat properly.

"It's hard to draw the link in a scientific way, but the low rates of survival for patients who live in Darwin speak to how hard it is for people to survive in those circumstances."

After the Daisy Y, Friday stayed with different families she knows in Darwin. Although more affordable, it was disruptive. "Too many drunks, too many people smoke ganja, you buy food and they eat all your food up," she said.

Moving in with family in public housing can cause other problems. "When public housing gets overcrowded, it’s not great living conditions, but it also can mean those relatives’ tenancy gets threatened," said Puszka. "There are very strict limits on visitors."

This year, Friday moved back to the Daisy Y. It’s a roof over her head, regular meals are provided (although she is sick of the sandwiches served for lunch), and she doesn't need to cook or clean. "There were just no other options," Friday said.

But the hostel has strict rules. Unauthorised visitors aren't allowed in the hostel. "They got a sign on the door: you got to wait outside if you want to visit your family," Friday said. "That's the rules. We don't make the decision, they do. But I don't know why." The rooms don’t have TVs, fridges or kettles, and the gate locks at 10pm (although night attendants are onsite to let in residents with bookings).

AHL residents have "little control over their lives", with limited disposable income (disability benefit recipients would be left with around $30 a day) and limited control over the food they consume and when it is served, according to Puszka's research brief.

Gundimulk Wanambi Marawili, a Yirrkala woman on dialysis since 2010, spent four years at the Daisy Y before ending up in public housing and then returning to her community. She told BuzzFeed News she would sometimes go back to the hostel at night after dialysis and find it difficult to source food. "The hostels are not suited to us dialysis patients," she said. "We can hardly sometimes talk or walk, and we need a carer, our own family."

While AHL does have two Darwin hostels catering specifically to medical patients, demand has increased, pushing people to multipurpose hostels designed for shorter stays like the Daisy Y.

"If you were staying there for a few nights for an appointment or something, then perhaps it might suit your needs," Puszka said. "But it wasn't designed as a long-term option, so it would be fantastic for [AHL] to look at their model and think about what they could do to improve it for long-term residents." Her paper also suggests a review of Centrelink's processing of DSP applications.

An AHL spokesperson told BuzzFeed News AHL was considering options to better cater for the growing need for long-term accommodation for medical patients across its hostel network, and that AHL had been in discussion with the Menzies Institute about Puszka's report.

"AHL looks forward to working more closely with Menzies Institute to identify ways in which the report’s findings can be used to seek government support to provide improved levels of amenity to medical residents. Initially, this could take the form of a demonstration project in 2019-20, with the support of experts in the field, to better cater to longer term medical resident needs," the spokesperson said.

As well, the spokesperson emphasised that AHL's mandate was to provide short-stay accommodation and it is not a housing provider. "Its Conditions of Stay (which include rules regarding visitors and furnishings onsite) are in place to protect the safety and security of residents during their stay," he said. He said the nightly fee has not increased in a number of years, and AHL was not in a position to lower its rates.

Even if she gets a government house, it wouldn't cure Friday's homesickness. She said: "I don’t really want to live in Darwin, I want to go home."